An Intro to Real-Time Machine Learning

Computing Features for Prediction

I’ve noticed a trend in the data processing world to move from processing data in batches to processing data continuously in a stream [1]. Although stream processing presents new challenges [2], teams make the transition to get real-time insights and make real-time decisions. This, in turn, can lead to a better user experience and create a competitive advantage.

Netflix is a premier example of a company that has taken the leap towards real-time data infrastructure [3, 4]. This has enabled Netflix to improve their user experience in a variety of ways, such as improving recommendations on the “Trending Now” home screen, rapidly testing changes in production, and minimizing downtime of the Netflix service [5, 6, 7, 8].

Meanwhile, the field of machine learning has also grown tremendously in the past decade. Machine learning models have become integral to the services offered by companies in a host of domains, including autonomous driving, dynamic pricing, and fraud detection. However, deploying these models effectively presents complex engineering challenges.

This post resides at the intersection of these two fields: real-time data infrastructure and machine learning [9,10]. This post is primarily intended for data scientists and machine learning engineers who want to gain a better understanding of the underlying data pipelines to serve features for real-time prediction. In particular, this post addresses three main questions:

- What is real-time machine learning?

- Why is real-time machine learning important?

- How do we compute features for real-time prediction?

What is real-time machine learning?

The critical component of real-time machine learning is the use of machine learning models to make predictions in real-time. Specifically, a prediction is made through a synchronous request and a response is expected to return immediately – on the order of hundreds of milliseconds, oftentimes less.

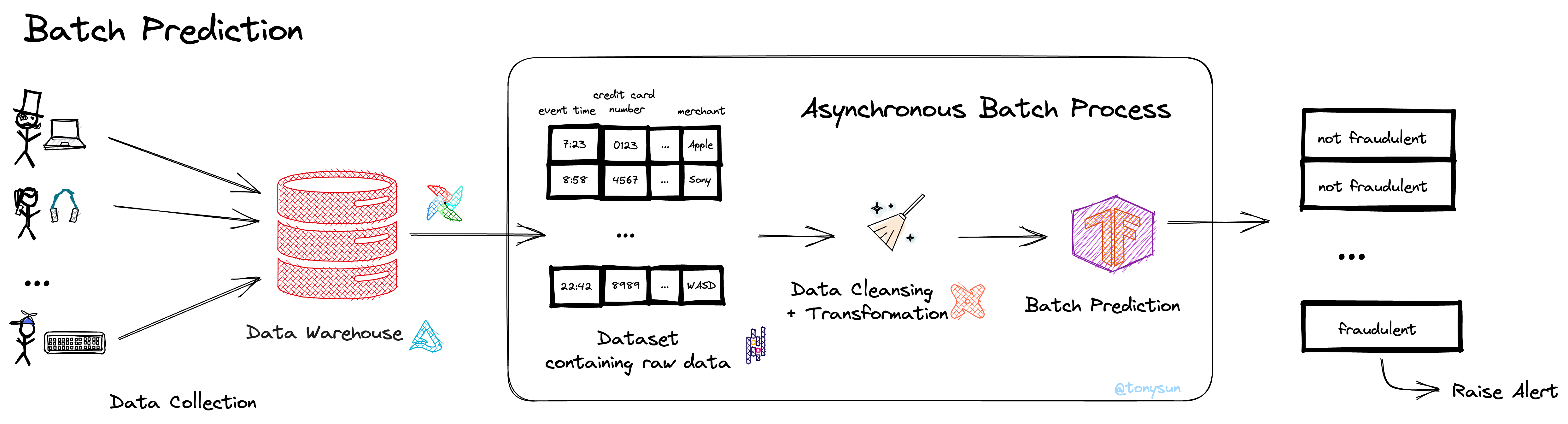

Contrast this to making predictions in batch, in which predictions are made on a large volume of data points all at once [11, *]. Predictions are made via a batch job. I have heard the term batch machine learning to describe this concept, although it doesn’t appear to be highly prevalent [12].

Let’s work with a fraud detection example. In this example, a consumer purchases a laptop online. The credit card network, say Visa, tries to detect whether the transaction is fraudulent or not.

Using the batch machine learning paradigm, predictions are made in batch. Here’s how that might happen:

- During the day, transactions are accumulated into a data warehouse.

- Periodically, say nightly, an orchestrator kicks off an asynchronous batch job that processes the data. The job involves extracting raw data from the data warehouse, cleaning and transforming that data into features, and making predictions in batch [13].

- For transactions predicted to be fraudulent, an alert is raised. However, note that these transactions have already been processed, so reversing them may not be trivial.

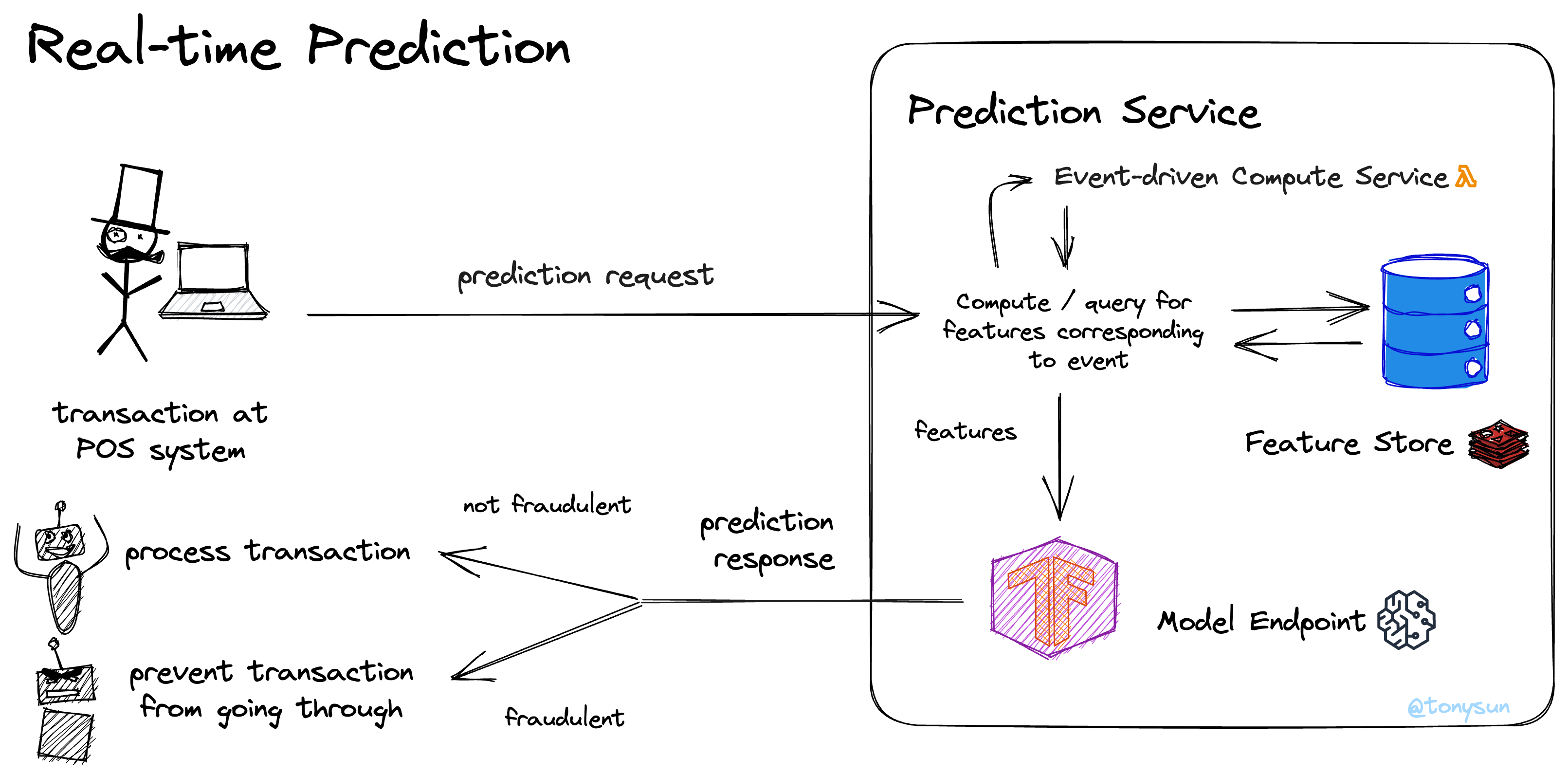

Using the real-time machine learning paradigm, a prediction is made in real-time. That might look like the following:

-

A transaction at a POS system triggers a request to a prediction service that predicts whether the transaction is fraudulent or not.

-

In order to make a prediction, the prediction service first needs to retrieve all the relevant features for the model.

a. Some features will be computed in real-time using information from the event itself.

b. Other features will be queried from the online feature store.

-

The retrieved features are passed to the model endpoint for prediction. If the transaction is predicted to be fraudulent, the transaction is flagged and prevented from going through.

Why is real-time machine learning important?

Before we dive into preparing features for real-time prediction, let’s first understand why real-time machine learning is important.

Real-time machine learning is powerful for its ability to help get real-time insights and make real-time decisions. This information and these choices are critical for some applications, improve user experience in others, and enable proactive responses in yet others.

In our example, flagging a transaction as fraudulent in real-time and preventing that transaction from going through is far more effective than trying to reverse a fraudulent transaction after it has been processed, which can be complex. Given that fraud detection is a $385 billion industry [15], any reduction in financial loss can be of significant magnitude.

Here’s a brief and by no means comprehensive list of some applications that benefit from real-time machine learning:

- Anomaly detection for fraud detection, network security, healthcare monitoring, and quality control.

- Personalized recommendations for marketing, e-commerce, and media and entertainment.

- Real-time decision making for autonomous driving, high-frequency trading, and robotics.

How do we compute in a real-time machine learning pipeline?

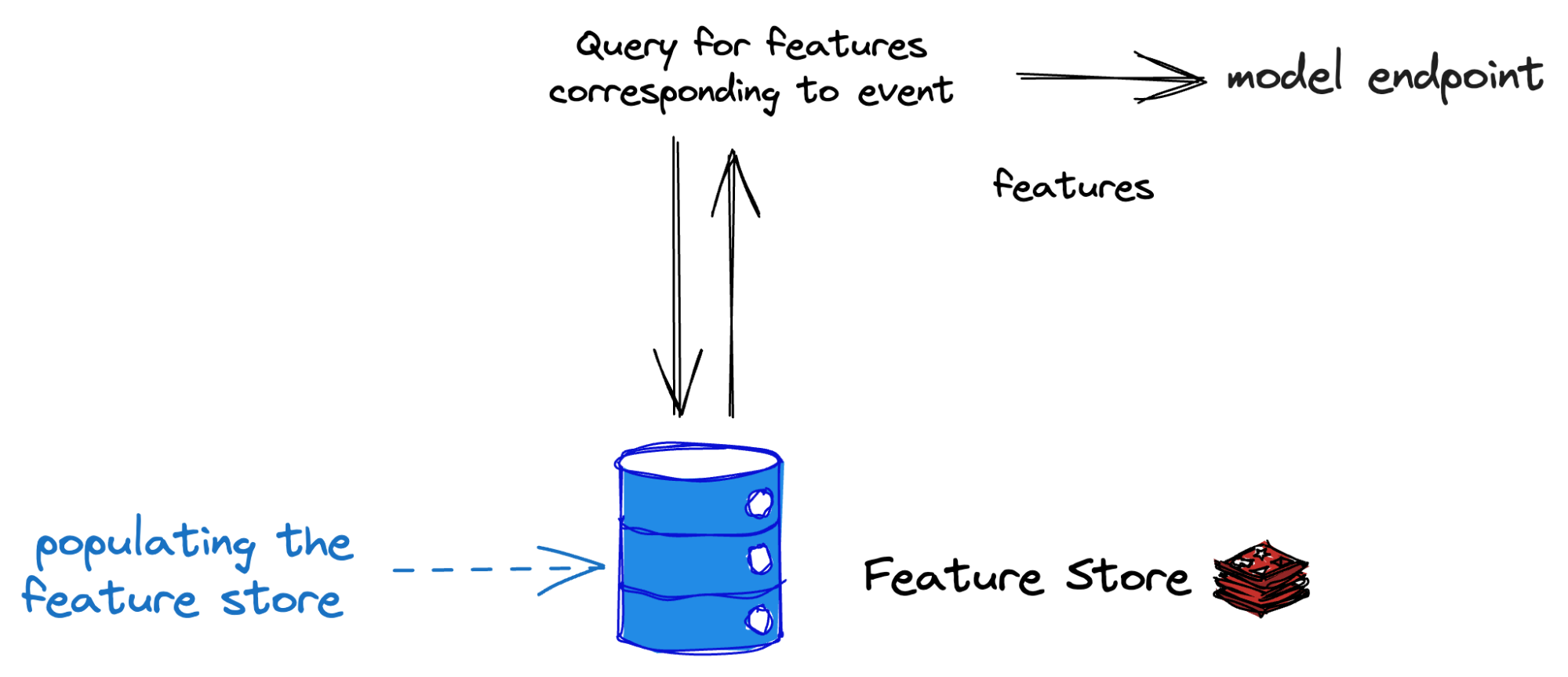

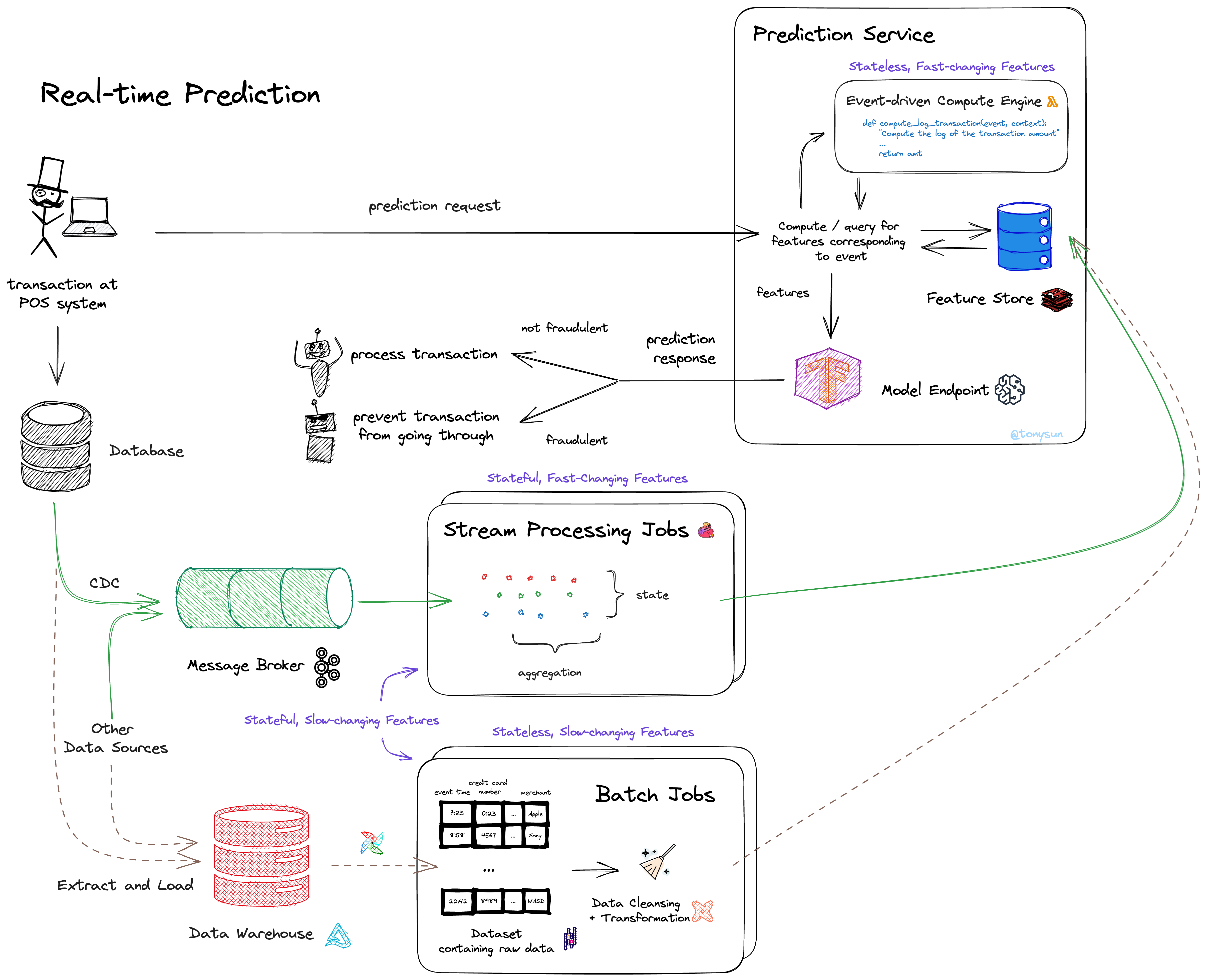

A prediction service is responsible for passing features to a model endpoint to perform prediction. Some of those features can be retrieved from an online feature store, while others may need to be computed in real-time.

The engineering challenges around preparing features for real-time prediction depend on the types of features we’ll be working with. We’ll first go over what an online feature store is and give an example of what it might look like. Then, we’ll categorize features into 4 groups and discuss which features are suited to being computed in real-time. Finally, for each of our feature groups, we present a basic system design for their computation.

Feature Store

Feature stores can vary in complexity, ranging from a simple repository of pre-computed features to a much more intricate system responsible for feature versioning, data quality monitoring, access control, and more.

The purpose of an online feature store is to reduce the latency of a prediction request. By computing feature values in advance, we save time that would otherwise be spent calculating these values during the prediction request. This makes our prediction service more efficient and enables us to handle higher volumes of requests in a scalable way [*].

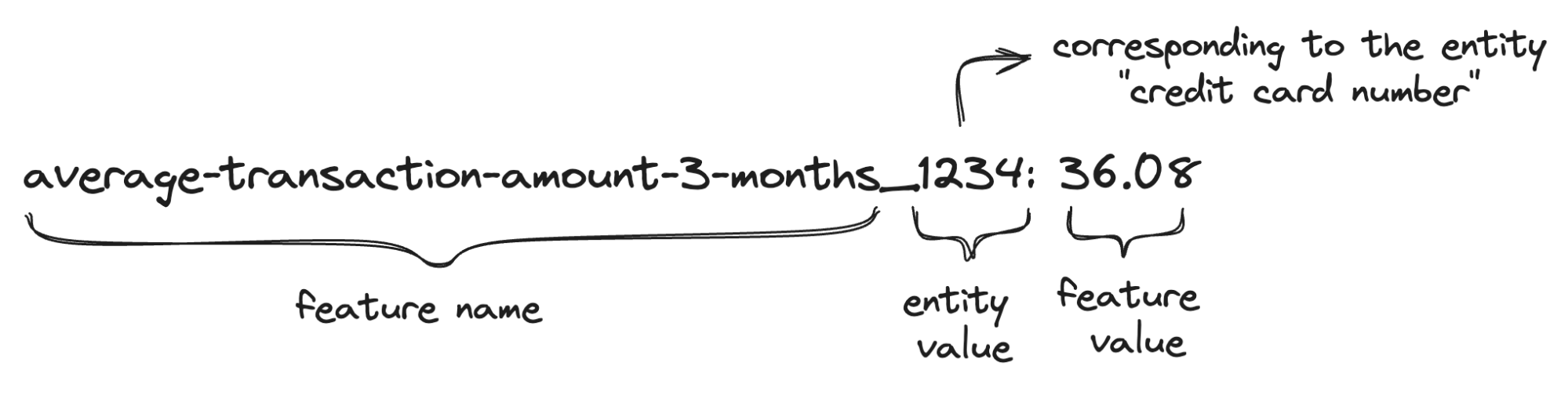

For our purposes, we will use a key-value store as our online feature store [16]. In our feature store, each key-value pair corresponds to a computed feature value.

Here’s what a key-value pair might look like: the key is a concatenation of the feature name and its corresponding entity value(s). The value represents a computed feature value.

For example, if the feature is the average transaction amount over the past 3 months, “credit card number” would be a natural choice for the entity of this feature. An example of an entity value could be “1234.” The computed feature value could be $36.08.

The entity of a feature relates to how the feature is being computed. One way to think about this is “feature of entity.” For example, I might care about the average transaction amount of a credit card number, or I might want to know the age of a customer. An entity value represents the specific instance of an entity, such as the actual credit card number of a user.

A feature can also have more than one entity. For example, the feature “average transaction amount with a given merchant over the past 3 months” would use both “credit card number” and “merchant_id” as its entities.

Real-time Prediction

At prediction time, we will need to query for the relevant features from the feature store. We just went over “feature store;” now, let’s clarify what we mean by “querying for the relevant features.”

- What are the features we should query for?

- How do we query for those features from the feature store?

What are the features we should query for?

The features we should query for naturally depend on the model we intend to use for prediction. Since the model is trained using a certain set of features, it requires those same features to do prediction.

For the sake of our example, let’s say our model was trained with just the following three features (represented as feature name: entity):

- customer_age: customer_id

- # of transactions in the past 10 minutes: credit card number

- average transaction amount in the past 3 months: credit card number

How do we query for those features from the feature store?

Our goal is to query the feature store (a key-value store in our example) for the features our model requires. For each of those features, we need to construct the corresponding key. In our example, we use a combination of the feature name and the feature’s entity value. The entity value will depend on the information observed in the event on which we aim to do prediction.

Say our transaction event looks as follows (represented as field name: value):

- transaction_id: a0d8

- credit_card_num: 1234

- customer_id: 9092

- …

- transaction_amount: 999.99

For the feature “customer_age,” we can query our feature store for the value corresponding to the key “customer_age_9092,” indicating the age of the customer with customer_id 9092. We do this for each feature.

The exception are features that can be computed using just information in the event. These features, such as “log(transaction amount)”, are computed separately in real-time and do not needed to written to or read from the feature store. We’ll drill in more in the following sections.

Types of Features

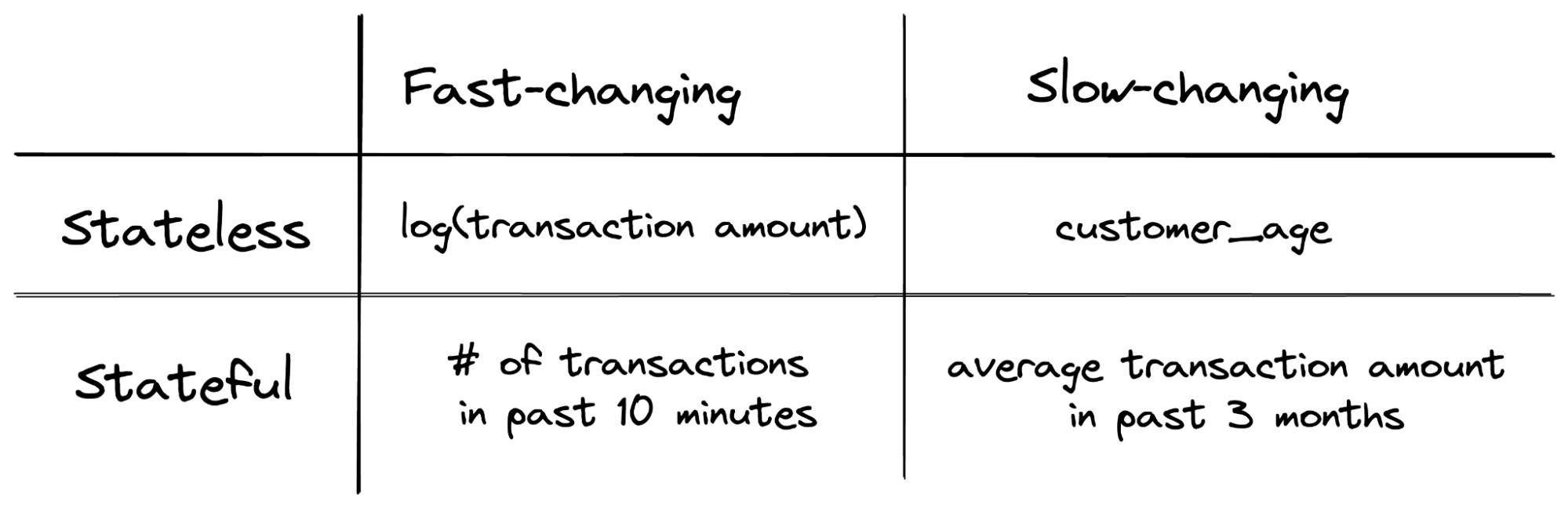

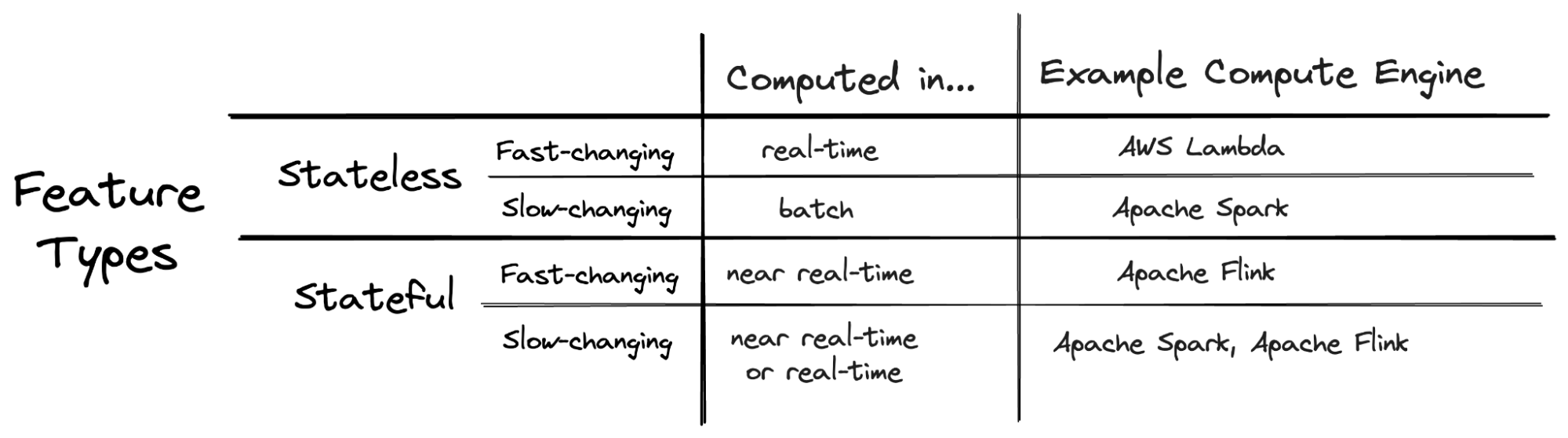

The most common way to categorize features is in terms of discrete (categorical) vs continuous (numerical). However, as a post focused on the engineering challenges of making features readily available for real-time prediction, I’d like to propose two new axes of categorization:

- Stateless vs Stateful

- Stateless features can be computed using stateless operations based on the information in the current event alone. The computation does not involve information from previous requests.

- Stateful features require knowledge about previous events or instances and require stateful computations. They maintain a “state” from the past [17].

- Slow-changing vs Fast-changing

- Fast-changing features are features that can change rapidly, even between events that are close together in time [*].

- Slow-changing features are features that don’t change, or change very slowly over time [*].

It may be tempting to think of fast-changing as stateless and slow-changing as stateful. However, this is not necessarily the case. Let’s categorize our previous feature examples:

- log(transaction amount): a stateless and fast-changing feature. Computing the log of the transaction amount changes with each transaction and requires only the information present in the current request.

- customer_age: a stateless and slow-changing feature. A customer’s age increments slowly. Although the “customer_age” attribute may not be in the prediction request, we can retrieve the value for this feature using information in the event (e.g. customer_id). This operation is considered stateless because retrieving this feature does not depend on previous requests.

- # of transactions in the past 10 minutes: a stateful and fast-changing feature. To compute this feature, we need to maintain a count of the customer’s transactions in the last 10 minutes. Furthermore, the count can rapidly change with every new transaction or when transactions fall out of the 10-minute window.

- average transaction amount in the past 3 months: a stateful and slow-changing feature. Computing this feature requires a record of the customer’s transaction amounts over the past 3 months. Although new transactions and the passing of time may affect this feature, the magnitude of the feature value will likely change slowly. This means that it may not be necessary to update this feature for each incoming event.

Populating the Feature Store

Each of the four types of features requires a different method of computation. We go over each feature type below:

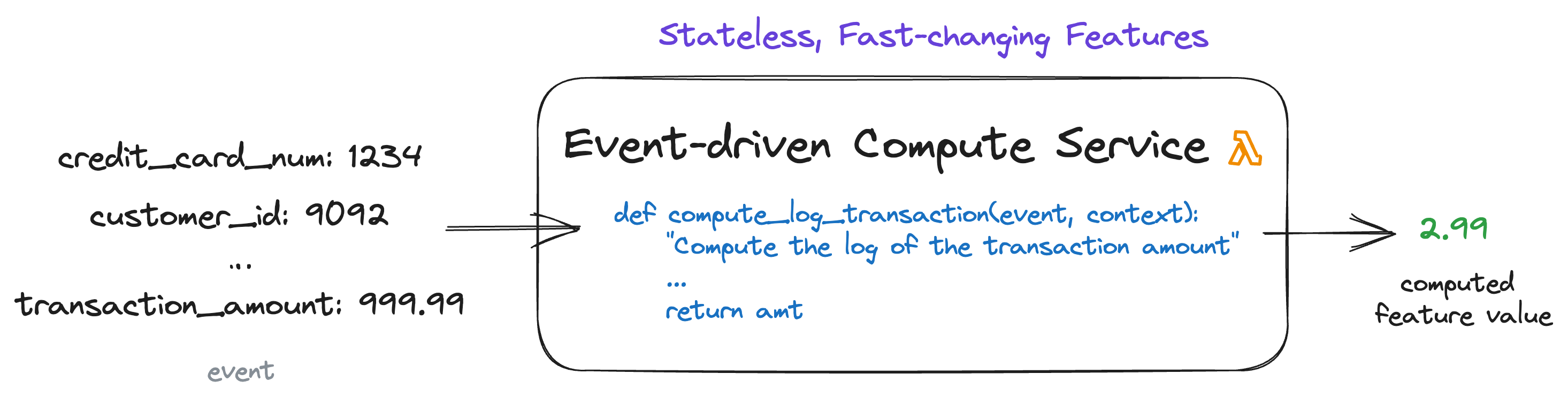

Stateless and Fast-Changing

Computing stateless and fast-changing features requires us to process each event on its own. For our “log(transaction amount)” feature, this involves extracting the transaction amount from the event and running a function that computes the log of a number.

This can be done through an event-driven compute service such as AWS Lambda.

Stateless and fast-changing features are also known as real-time features because they are computed on-the-fly, in real-time.

Something unique about stateless and fast-changing features is that they are not fetched from the feature store, which only stores pre-computed values. This also means that the entity is not relevant for these features.

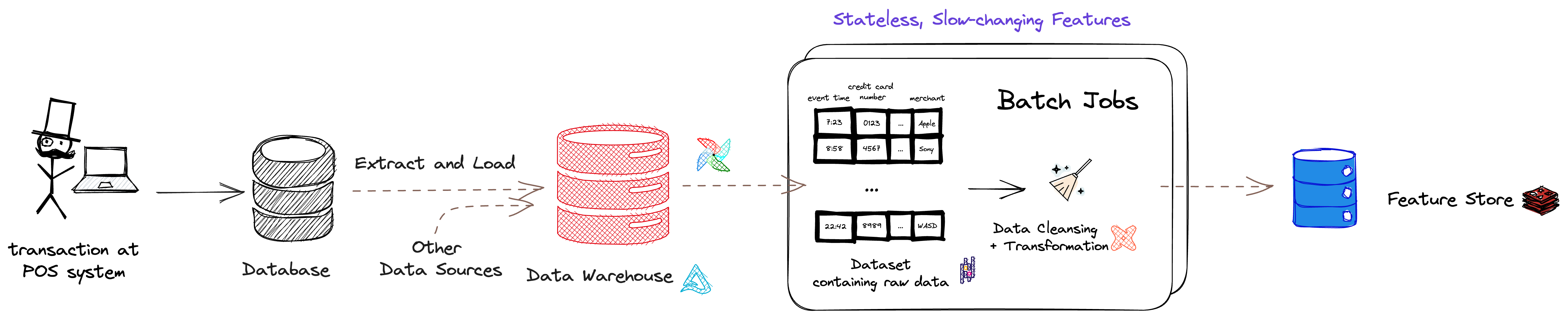

Stateless and Slow-Changing

Similar to stateless and fast-changing features, we can compute stateless and slow-changing features in real-time, at the time of prediction. However, because these features are slow-changing, the prediction request may not have the full information for computation.

Take the “customer_age” feature as an example. Because the age of a customer only changes once a year, it may not make sense to include this information in each prediction request. Instead, the customer age may be stored in a database somewhere, and we’ll need to fetch this information using the “customer_id” in the prediction request.

For this reason, it makes sense to pre-compute stateless and slow-changing features and load them in the feature store well ahead of prediction time. Features that best fit this category include those involving common database queries where the results rarely change. It may be useful to think of storing pre-computed features in the feature store as caching the results of a query.

Here’s an example of how the computation might happen. A transaction that triggers a prediction request is also written to a database. Data in that database, along with data from other data sources, may be periodically extracted and loaded into a data warehouse.

Computing stateless and slow-changing features may involve retrieving a subset of data in that data warehouse and doing any stateless data cleansing and transformation if necessary. This can be done via batch job(s) that can be kicked off periodically by an orchestrator, and the computed feature values are written to our online feature store. The dotted brown arrow in the figure below indicates that the data is processed periodically.

Stateless and slow-changing features can also be considered batch features because they are typically computed in a batch process. The pipeline might look similar to our batch prediction pipeline earlier, except we stop before the model prediction part and instead store the features into our online feature store.

The computation can be done through a batch engine such as Apache Spark. Using a batch engine offers benefits in terms of robustness and efficiency. Spark is fault-tolerant which means it can recover from failures and errors without losing data or functionality. Spark jobs can also scale horizontally, ensuring timely processing even as the size of the data grows [*].

However, one downside of pre-computing features in a batch process is the need for excess computation and storage. Because we don’t know which entity values will be encountered at runtime, we would need to compute the feature values for all possible entity values. Depending on the traffic pattern, many computed feature values may go unused, wasting computation and space in the feature store.

In our example, we would need to load the age of all customers into our feature store. However, if the cardinality of our feature is high (there are many unique customer IDs), doing so may not be practical.

An alternative would be to query for the feature value at runtime, reducing the number of features stored in the feature store at the cost of increasing prediction latency. A practical solution could be to pre-compute features for the most frequently used entity values and compute the feature value for less frequently used entity values in real-time.

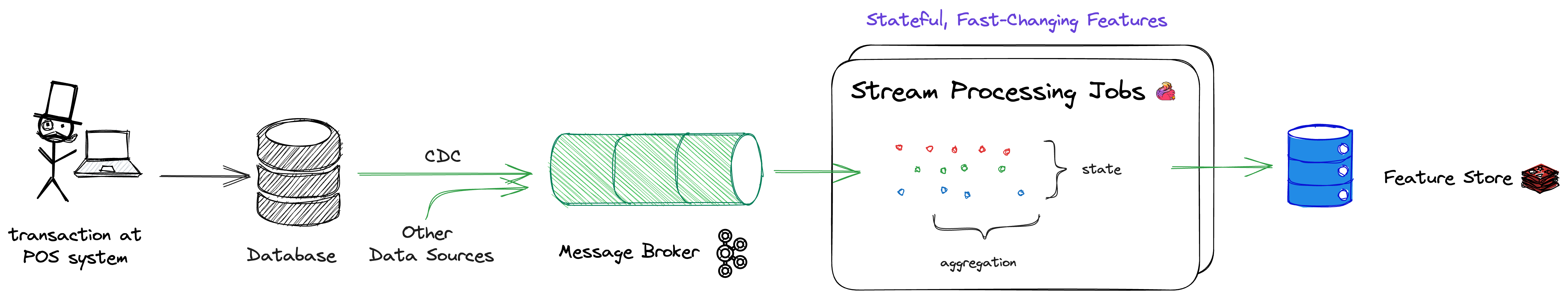

Stateful and Fast-Changing

Computing stateful and fast-changing features requires a stream processing engine, such as Apache Flink. This will help us with state management when dealing with a continuous flow of information.

A stream processing engine facilitates real-time data processing of incoming data streams. While batch processing is efficient for processing large, static datasets, it’s not designed to handle the dynamic nature of stateful and fast-changing features [*].

For our stateful and fast-changing feature “# of transactions in the past 10 minutes,” [18] we would also need to be more precise about when the feature is computed. This leads us to the concept of windowing, which is a critical component of stream processing. Here are three different options [19, 20]:

- Tumbling window: compute the feature every 10 minutes (same as the window size of the feature).

- Sliding (hopping) window: specify another duration, less than ten minutes, for how often we want to compute the feature. For example, we might want to compute the feature every minute. This means that the feature is updated more frequently and the computation windows overlap [*]. A tumbling window is a special case of a sliding window where the slide size is the same as the window size.

- Per-event: compute the feature for each incoming event.

If stateful and fast-changing features are computed with a tumbling or sliding window, they can also be considered near real-time features, because they are computed shortly before prediction time. However, if the feature is computed at prediction time, as when computing per-event, this feature would be considered a real-time feature.

Computing per-event makes sense when the entity value of the feature appears infrequently. For example, if the credit card number of the feature appears infrequently, then using a sliding window can lead to computations where the result is unchanged. Conversely, computing features using a sliding window results in lower latency at prediction time and can be more computationally efficient when the entity value appears frequently, at the potential cost of a slightly inaccurate feature.

Let’s go over our example. The transaction that’s written to a database is converted to an event in a message broker via a process known as change data capture (CDC). That event, along with events from other data sources, are processed by a set of stream processing jobs. The computed feature values are written to our online feature store. The green arrow in the figure below indicates that the data is processed continuously.

Compared to batch processing, stream processing can be more complex due to challenges around event time skew, state management, and unbounded data, to name a few [21].

An alternative is micro-batch processing (basically batch processing in small, discrete chunks), though it may not be a practical one. Here are a couple reasons why:

- Resource Consumption and Efficiency: Micro-batch processing often has higher resource overhead than stream processing because of the constant creation and destruction of small jobs [*]. Additionally, if multiple batches include similar data or require similar processing steps, maintaining a long-running stateful job with stream processing may actually be more resource efficient. We go over an example in the section below.

- Latency: While micro-batch processing can reduce latency compared to traditional batch processing, it can’t match the low latency provided by true stream processing engines like Apache Flink [*].

- For instance, performing computations per-event with micro-batch processing would require spinning up a new job for each event, which is not really feasible for real-time prediction.

Stateful and Slow-Changing

Stateful and slow-changing features have the most flexibility in terms of how they are computed.

Since these features are slow-changing, it might make sense to compute them in batch. However, that isn’t to say that these features can’t be computed in near real-time or even real-time with a stream processing engine as well.

One factor to consider is the freshness requirements of the feature. If a slightly stale and outdated value for the feature is acceptable, then batch processing could be sufficient. “Staleness” in this context refers to when the feature was computed relative to the event time. The greater the gap, the more stale the feature value is.

Staleness matters for two reasons:

- Exclusion of recent data. If recent information is important to how the feature is computed and model performance, it may be critical to have fresh data.

- Train-prediction inconsistency. If the model was trained with features computed at the time of event but uses stale features at the time of prediction, this can lead to worse model performance. Ensuring train-prediction consistency is a nuanced point and will be explored more in-depth in the next post.

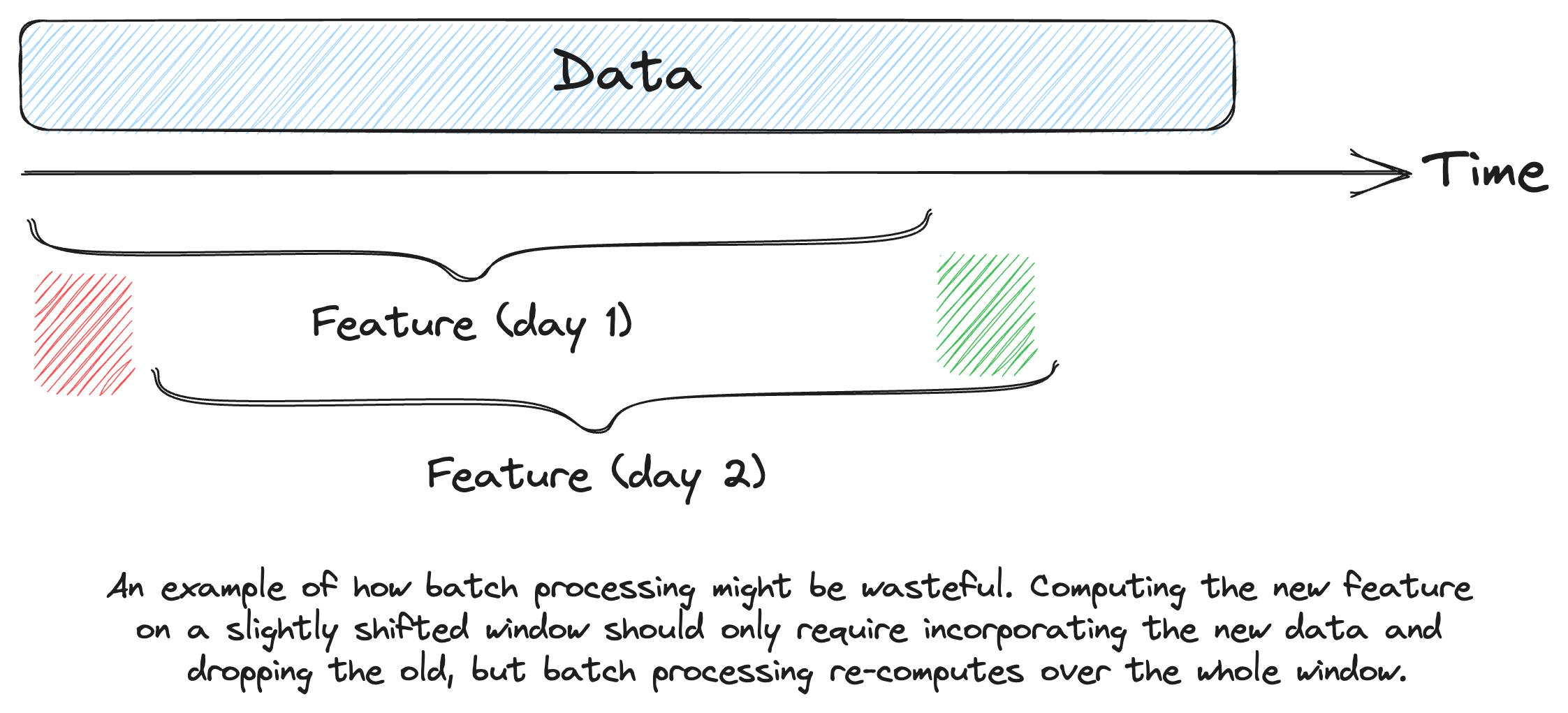

Another consideration is how much repetitive computation will be performed during each batch. For example, if my feature is computed on data from the past three months, re-running a batch job to compute that feature every night can be wasteful [22]. In such a scenario, a stateful, long-running streaming job can actually lower costs.

Making the choice between a batch versus streaming engine for feature computation will likely depend on the use case at hand. Personally, I believe that stream processing is a more general version of batch processing, so it makes sense to move towards stream processing in the long-run. However, the data infrastructure around stream processing and real-time machine learning is still a developing field, so working with established batch engines and tools may be a more practical choice.

Derived Features

Derived features are features that build upon other features. For example, say that in my data exploration process, I find the feature “Z-score of transaction amount” to be predictive of fraud. After all, a transaction amount 3 standard deviations above the mean would be quite alarming.

How the derived feature is computed naturally depends on how the underlying features are computed. In our example, computing the mean and standard deviation of the average transaction amount in the past three months can be considered to be stateful and slow-changing features. We could compute these two features with either a batch or streaming engine. Once in the feature store, we can use an event’s transaction amount and combine it with the mean and standard deviation in a lambda function to compute the Z-score.

Summary

Put it all together, and this is a more complete depiction of real-time machine learning system with data pipelines that prepare features for prediction:

Conclusion

I hope you learned something about real-time machine learning from this post. We started with a high-level overview before diving into stateless vs stateful and fast-changing vs slow-changing features. For each of the four types of features we discussed, we presented a simple system design for their computation.

A key takeaway is the tradeoffs between correctness, cost, and latency. Computing features in real-time guarantees the correctness of the computed value at the cost of increasing latency at prediction time. On the other hand, computing features in near real-time or batch and storing those values in an online feature store helps us reduce latency at prediction time at the cost of slightly inaccurate feature values. Cost is oftentimes a function of the solution we fit to our problem, and we discussed ways to improve cost efficiency.

However, preparing features to be used for real-time prediction is only half the story. We also need to go over how to prepare features for training the right way, to avoid potential problems like train-prediction inconsistency. This will be the topic of my next post, so stay tuned.

In the meantime, I’m always learning more about real-time machine learning. If this post resonated with you, I’d love to hear from you.

Terminology

real-time prediction = online prediction; batch prediction = offline prediction

The terms “real-time prediction” and “online prediction” are often used synonymously [14]. Similarly, “batch prediction” and “offline prediction” are interchangeable. I have a preference for the terms “real-time” and “batch” over their counterparts, “online” and “offline,” respectively, from the clarity they provide on the nature of the prediction process [*].

Real-time Prediction Terms

Event Broker: kind of like a post office for software, accepting messages (events) from one part of a system (producers) and delivering them to other parts of the system (consumers) [*].

Feature store: a database that serves as a central repository for storing, managing, and serving machine learning features [*].

Prediction Service: the infrastructure and related services set up to use a machine learning model for making predictions [*]. In our example, this includes querying the online feature store and passing those features to a model endpoint.

Model Endpoint: the network interface exposed by a deployed machine learning model, typically via a RESTful API, to receive and respond to prediction requests [*].

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Zhenzhong Xu, Chip Huyen, Marina Zhang, Rhythm Garg, and Andrew Gaut for reviewing early drafts of this post.

Appendix

* The asterisk represents text that I’ve added with the help of a LLM such as GPT or Bard.

[1] A Google Trends graph of web searches for stream processing (red) vs batch processing (blue) in the past 10 years. At the moment, batch processing is still more prevalent than stream processing, although the gap between the two has shortened over time.

[2] Some new challenges around stream processing include the need to handle unbounded data streams, out-of-order data, and stateful computation, to name a few.

[3] The Four Innovation Phases of Netflix’s Trillions Scale Real-time Data Infrastructure

[4] Netflix Tech Blog: Stream Processing

[5] What’s trending on Netflix?

[6] Stream-processing with Mantis

[7] Keystone Real-time Stream Processing Platform

[9] Machine learning is going real-time

[10] What Is Real-Time Machine Learning?

[11] Batch predictions

[12] A quick search online for the term “batch machine learning” leads to more results around the batch size for model training as opposed to batch prediction.

[13] You Don’t Need a Bigger Boat is also a good resource.

[14] I’ve seen “model prediction” and “model inference” used interchangeably. Both refer to “the process of running data points into a machine learning model to calculate an output such as a single numerical score” [Model inference overview] . I personally prefer to use the term “model prediction.”

From a statistical perspective, inference and prediction actually mean slightly different things. Inference refers to the “study of the impact of factors on the outcome.” For example, inference aims to answer questions such as “What is the effect of age on surviving the Titanic disaster?”, whereas prediction aims to answer questions such as “Given some information on a Titanic passenger, you want to predict whether they live or not and be correct as often as possible” [What is the difference between prediction and inference?, An Introduction to Statistical Learning].

[15] Operationalizing Fraud Prevention on IBM z16

[16] Building a Scalable ML Feature Store with Redis

[17] For stateful features, the entity (credit_card_num) corresponds to the field used by the GROUP BY clause if we were to compute the feature at a given point in time:

SELECT credit_card_num,

AVG(amount) AS avg_transaction_amount

FROM transactions

WHERE transaction_date >= DATE_SUB(CURDATE(), INTERVAL 3 MONTH)

GROUP BY credit_card_num;

[18] A session is another type of window, but the beginning and end depend on user behavior.

[19] Windowing TVF

[20] Over Aggregation

[21] Streaming 101: The world beyond batch

[22] The idea for the diagram is stolen shamelessly from Chip’s continual training graphic.